If you’ve been on Reddit or TikTok in the past year, you may have seen threads like “is Gen Z aging like milk?” go viral. If you’re unfamiliar with this slang (I was), the question is asking if Gen Z is aging faster, because milk curdles and spoils quickly. The point is that people are wondering why younger generations look older.

Maybe it’s the tube socks with open-toe sandals trend…?

Fashion aside, there’s been a real conversation lately about whether younger generations are actually aging faster. Let’s dig into the science behind that idea.

While it is difficult to find studies that look at aging across generations, in 2018, a study using national data got a lot of attention. It found that people were aging slower in more recent times (2010) compared to the late 1980s, and this trend was seen across all age groups. But it is important to note that the study looked at differences across age groups, not generations. Using some basic arithmetic, I calculated that Millennials were in their 20s and Gen Z in their pre-teen/teen years in 2010. So, Gen Z was not represented because you had to be 20 or older to be included in the study. Millennials were included, but they were lumped in with Gen X, so it’s messy and doesn’t give us a clear picture of what is happening. So, moving on.

Another way to tell if younger generations are aging faster is to look at whether they are developing diseases that we typically associate with old age. Here we do find some evidence. Recent research suggests that an increasing number of young people today are being diagnosed with chronic conditions we usually associate with old age, like cancer, stroke, or even heart failure. More young people are also dying of these conditions.

As a scientist who studies aging and health across the lifespan, I want to break down what might be going on, starting with a basic concept that can change how you think about your health:

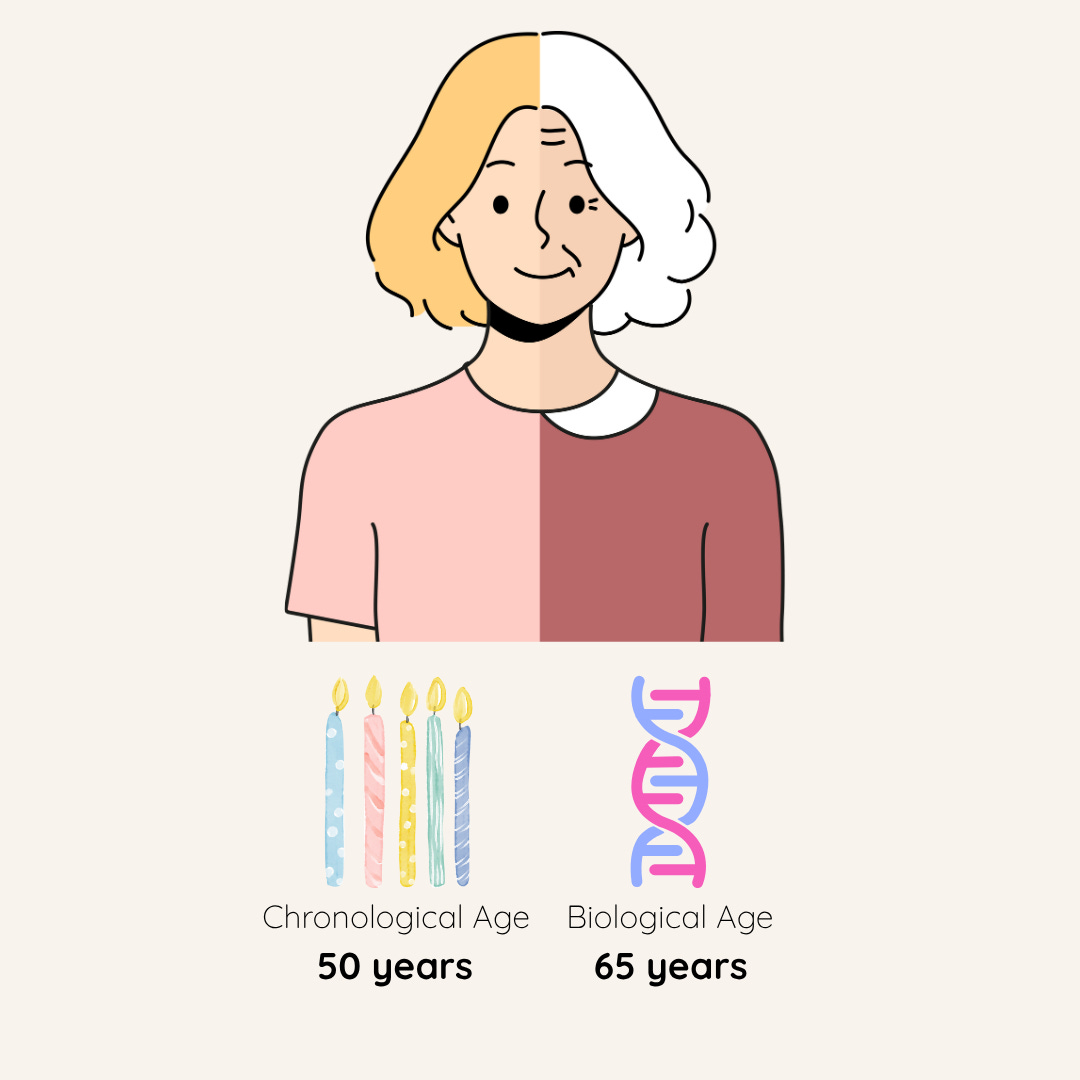

Chronological age ≠ Biological age

Your chronological age is how many candles are on your birthday cake. Easy.

Your biological age is how old you are on the inside. It reflects aging at the cellular level, not necessarily the passage of time.

So, your birthday cake may have 50 candles, but on the inside, you might be 60. That is what we call an accelerated ager, someone who is biologically older than their chronological age. They may have more visible signs of aging, like wrinkles, gray hair, and have developed chronic diseases, fatigue, or memory problems compared to other 50-year-olds.

Or you might be 40 on the inside. That is what we call a slow ager, someone who is biologically younger than their chronological age. They may look more youthful and be more energetic, mobile, and cognitively sharp than a typical 50-year-old.

Why Does This Matter?

A person’s biological age is a better predictor of chronic disease risk (cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, dementia, some cancers), disability, and early death than their chronological age. In fact, biological aging explains why two people of the exact same age can have vastly different health. For example, take two 70-year-olds. One may be running marathons, while the other is wheelchair bound.

Usually, it is hard to detect differences in the health of young people. Why? Because not as much time has passed, and it takes time for cellular damage to show up as visible signs of aging. But this trend seems to be shifting.

Gen Z themselves has noticed that they look older than millennials and science tells us that perceived facial aging (whether you think someone’s face looks older) is correlated with biological aging. Researchers are also sounding the alarm with more papers showing that chronic diseases of mid and late life are increasingly being diagnosed in younger people (e.g., colon and breast cancer).

So, it is possible that the visible aging and divergence in health that we are seeing among younger people is happening because some are biologically aging faster than others.

Note: If you are interested in learning more about why people might be developing some cancers at younger ages, my colleagues and I recently published our hypothesis in JAMA Oncology that faster aging may be driving this phenomenon.

What Could Be Driving Faster Aging in Younger People?

Although we are not totally sure why some young people are developing some chronic diseases earlier than usual, we do know that certain stressors accelerate biological aging. Things like:

Excess weight

Sedentary lifestyles (hello, 12 hours of screen time)

Smoking

Alcohol

Chronic stress

Poor sleep

Depression

Loneliness and social isolation

Adverse childhood experiences, like abuse

Environmental exposures, like pollution

It is possible that younger generations are being exposed to these stressors earlier and more often than previous generations.

Can You Slow It Down?

Yes! The good news is that biological aging is not fixed. There are tangible things you can do to slow it down, and maybe even reverse it. My advice would be to focus on the anti-aging lifestyle practices within your control. Some examples may include:

Exercise

Prioritize sleep

Quit smoking, if you smoke

Create and maintain social connections

Manage stress in a healthful way that works for you – mindfulness/meditation, therapy, exercise, time in nature, journaling, etc.

What’s Next?

Starting next week, I am going to do a three-part deep dive on biological aging – what it is, how you can figure out your ‘real’ age, and what you can do about it.

If you have specific questions you want me to cover, subscribe and leave a comment or DM me.

Final Thoughts

It is important to note that for now, this idea that Millennials and Gen Z are aging faster remains a hypothesis that needs to be proved or disproved. The first step is to show that younger generations are increasingly developing conditions of old age (check).

The next step is to gather scientific evidence that measures biological aging in young people and then link that biological aging to the early development of these conditions. I imagine in the coming years we will start to see many papers on this.

Younger generations may be aging faster than previous ones, but it doesn’t have to be that way. So go ahead and rock the tube socks and sandals, if you must. Just pair them with some movement, sleep, and socializing to optimize your biology for aging well.

💌 Subscribe to learn more about how longevity science can help you live longer and better.

For your reading pleasure:

· Levine and Crimmins, 2018, “Is 60 the New 50? Examining Changes in Biological Age Over the Past Two Decades.” Demography.

· Guida, Gallicchio, & Green, 2025, “Are early onset cancers an example of accelerated biological aging”, JAMA Oncology.